Up to 4 million people in and around Damascus, the Syrian capital, have gone without water for a week. But this terror attack and resulting crisis have barely registered in the international media.

Most of Damascus relies on two springs 15 miles northwest for its water. The springs are currently controlled by rebels with links to al-Qaeda. Last week, municipal authorities cut the water supply, accusing these al-Qaeda affiliated militants of poisoning the springs with diesel.

Imagine what a week without clean water would be like.

Most houses in Damascus—like my home in Iraq—get their water from large, rooftop storage tanks. Municipal authorities provide water (often intermittently) so you can fill your tank and draw from it to shower, wash, and drink.

But if the water supply is cut off, your tanks go dry.

My family and I have gone without water in our home for a few days before, and I can tell you: it is terrible. Nothing makes us want to leave the Middle East and never come back like running out of water.

You can’t do your dishes. You can’t do laundry. You can’t shower. You have nothing to cook with. You can’t flush your toilets. The risk of disease skyrockets.

You buy all the bottled water you can—if you have the means. But for many, especially the poor, this can be a crushing burden.

Yesterday, I spoke with a friend who lives in an upscale area of Damascus. “I’ve had no water for seven days,” she said. “People [with means] have to go to the gym [and draw from private water wells] to have a shower. So imagine those who have nothing.”

“If the situation continues,” she added, “we will end with the disease.”

There isn’t enough clean water or enough water trucks left in Damascus to distribute water to all the homes that have been cut off—and besides, people have to pay for water from these trucks.

Local authorities are distributing water in the city center, but the outer areas of Damascus are only served every couple of days.

“You can live without electricity,” my friend in Damascus told me, “but without water—it’s so hard.”

Differentiating Between Terrorists

So why is hardly anyone talking about an al-Qaeda-linked terror attack on 4 million people in and around Damascus and their water supply? Why isn’t it making headlines around the world?

If it were Paris or Brussels or New York—and terrorists poisoned the water supply, forcing it to be shut off—it would be all over the news. If this happened anywhere else, it would be called an act of terror, no matter who was in charge.

But this is Damascus, and Damascus belongs to Bashar al-Assad. And because he isn’t exactly a sympathetic figure, and because there is no love lost between the West and Assad, there is no sympathy for all the ordinary people of Damascus, either—those who are caught up in this brutal conflict.

There is no sympathy for people who just want to live in peace, who just want to give their children something safe to drink, who want what many of us take for granted.

It’s guilt by association. And this dangerously simplistic “good guy vs. bad guy” narrative is causing us to turn a blind eye to real human suffering.

Bottom line: If it looks like a terrorist and acts like a terrorist, we should call it a terrorist. Period. When someone poisons an entire city’s water supply, it’s an act of terror—whether that city is Damascus or New York.

That may not change how we feel about the other parties in the Syrian conflict—in fact, that’s precisely the point. For too long, the U.S. has made an artificial, self-serving distinction between terror groups, coming down hard on some while turning a blind eye to others. So have other players in Syria, for that matter—like Turkey and Russia, for example.

Terror is terror. Violence against civilians is detestable, no matter who the perpetrator is. We should have the moral courage to name it.

Some dismiss charges that the US treats terror groups differently, calling them “ludicrous.” But we lend credence to these charges when we look the other way while a city is poisoned, or when we ignore Kurdish terrorism in Turkey because we support the same groups in Syria.

Like we’ve said before, if you want to know what side of the conflict we’re on, we’re on the side of families whose lives have unraveled because of violence. We’re on the side of bombed-out, on-the-run, desperate children who’ve lost everything. We’re on the side of those at risk of dying for lack of clean water.

We’re on the side that shows up to feed and clothe those who need it most. We don’t ignore the divisions—religious, sectarian, or political—but we choose to love anyway.

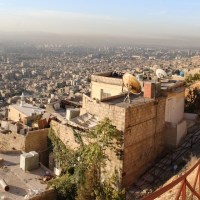

We’re on the side of people—in Aleppo, Damascus, and wherever there is need.

Where is the rest of the world when the water runs dry in Damascus?